Previous episodes of Stories From the Borderland have already considered how both the comics industry and Hollywood shamelessly plundered the old pulps for story ideas. Theodore Sturgeon’s “It!” (1940) spawned a long lineage of comic book swamp monsters, beginning with Heap in 1942, while the illicit progeny of Joseph Payne Brennan’s “Slime” from The Blob on down are almost as numerous. At least “Who Goes There” received credit in three out of four film adaptations—although “The Crawling Horror” did not, even when it was ripped off directly in a comic story with the same title in the November 1954 issue of Terror Tales.

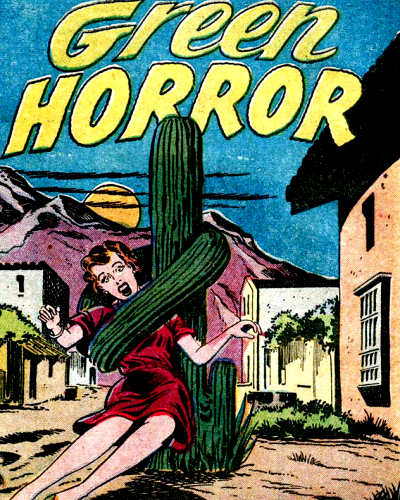

“Green Horror,” the tale of an overly amorous and aggressive cactus and the object of its unwholesome and unwelcome attentions, first appeared in the July-August 1954 issue of Fantastic Fears, only a few months before the Comics Code Authority poured its stifling load of cold wet cement over the entire medium in October 1954. Eerie Publications later reprinted the story in the November 1970 issue of Horror Tales. By that time, Eerie’s entire lineup, like Bill Gaines’ MAD magazine, had made the transition to magazine format in order to circumvent the Code.

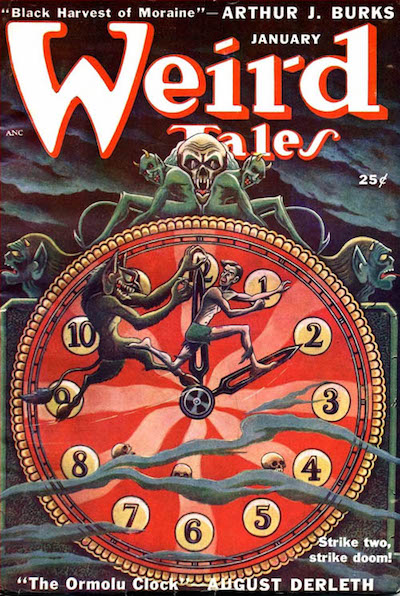

From “Come Into My Parlor” and Audrey Junior to “The Seed From the Sepulchre” and John Wyndham’s triffids, I have long loved a good weird plant story. Sadly, “Green Horror” is neither very good nor very weird. More importantly, it is not very original—and although the most recent installment of Stories From the Borderland argued at length for the primacy of storytelling over originality, “Green Horror” fails in both regards, being nothing more than a blatant rip off of “The Cactus,” a story by Mildred Johnson from the January 1950 issue of Weird Tales.

Johnson was an enigmatic author who published only a pair of stories, both in The Unique Magazine. Her second outing, “The Mirror,” was a serviceable ghost story, but “The Cactus” is truly Weird. Each story saw a handful of reprints, and if not for those, she might be forgotten entirely. Was “Mildred Johnson” a pseudonym? Why was her output limited to two stories published only a few months apart? Research dead ends at Weird Tales, with at least one major list of supernatural plant stories omitting “The Cactus” entirely, so we must know her by these two stories alone.

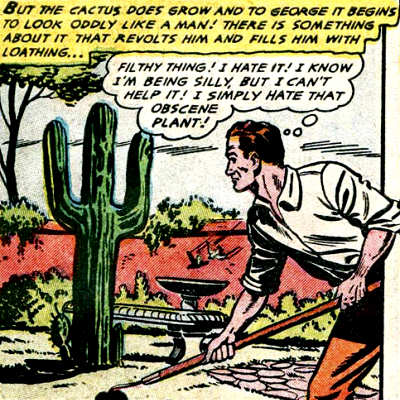

“Green Horror” retains enough of “The Cactus” to make its origins obvious, but it discards all that gave Johnson’s story its weirdness. A comparison of the two stories therefore offers a valuable opportunity to delineate some of the elements of a good weird tale. Where Johnson demonstrates an admirable grasp of what Keats called “negative capability,” suggesting without defining and allowing mystery to manifest on its own terms, the uncredited comic adaptation strips out the unexplained and moves subtext to the center of the narrative where it becomes ridiculous and cliché.

“Green Horror” retains enough of “The Cactus” to make its origins obvious, but it discards all that gave Johnson’s story its weirdness. A comparison of the two stories therefore offers a valuable opportunity to delineate some of the elements of a good weird tale. Where Johnson demonstrates an admirable grasp of what Keats called “negative capability,” suggesting without defining and allowing mystery to manifest on its own terms, the uncredited comic adaptation strips out the unexplained and moves subtext to the center of the narrative where it becomes ridiculous and cliché.

Both versions of the story begin with an American couple stopping in an isolated area of northern Mexico, where the wife takes a cutting from a large cactus. The cactus in the comic version is a simple saguaro, while Johnson’s cactus is something weirder, one of a horde growing within what appears to be a meteor crater like the one in Arizona: “a scoop in the earth, like a great dimple.” The reader is left to decide whether these prodigious growths are some earthly varietal mutated by the uncouth properties of whatever fell out of space, or the genuine products of panspermia. Johnson’s crater cacti also exude a sweet, musky aroma from their flowers, a smell that seems as irresistible to human women as it is repugnant to their men, although this aspect is never made explicit either. “Green Horror” abandons such weird nuances and is a much lesser story without them.

Johnson’s “The Cactus” may itself draw on O. Henry’s better known 1902 tale by the same title. Any potential parallels are vague, but the stories share a common tone—a tone that becomes far bleaker in Johnson’s rendering. If O. Henry’s story provided the essential cutting from which Johnson’s grew, the root of that allusion most likely lies in the Spanish name of Porter’s plant, which applied to Johnson’s “The Cactus” would add a deeper, creepier resonance to the tale’s sexual subtext.

As a resident of the U.S. American Southwest, I should at this point interject some factual remarks about the iconic saguaro. Although I often encounter souvenir merchandise from locales here in the high desert of the Colorado Plateau emblazoned with saguaros, their actual range is restricted to the Sonoran Desert, which means they occur naturally only in the southern portions of Arizona and California and the Mexican state of Sonora. Johnson sets her tale “about a hundred miles from Chihuahua,” which would place her crater and her cacti solidly within the state of Chihuahua (whose eponymous capital lies near its center) and the Chihuahuan Desert, whose flora are distinct from those of the warmer Sonoran zone to the west. Technically then, her cactus cannot be a saguaro. “The Cactus” is further distinguished by “liverish” flowers—saguaro flowers are white—and by two decidedly un-saguaro-esque “spikes” protruding from its crown. Whether Johnson’s botanical knowledge was significant enough for her to make these distinctions deliberately must also remain an enigma, but the spikes in particular—and her emphasis on them—suggest she meant her cactus to be something distinctly other.

Edith’s cutting thrives, as does Abby’s in L.A., though in both cases men all find it repugnant. We learn via letters that Abby’s husband Robert develops a bona fide hostility toward this vegetal intruder in his home, while Edith’s handyman Mr. Krakaur tolerates her specimen, though he proclaims it “Stinks like a goat.”

As much as social mobility was shaking up in the postwar era, the lives of American women remained highly constrained c. 1950, and their available hobbies were few. Cultivating exotic plants was one socially acceptable and popular option. I recall clearly my maternal grandmother’s collections of both cacti and African violets, both of which I referenced in my story “Do You Like to Look at Monsters?” Her violet collection extended over two long walls of her cellar, while her cacti were amassed in the children’s playroom, some suspending their tentacular arms down the front of her piano. In retrospect, it seems a miracle that neither I nor any of my cousins ever had an adverse encounter with any of these spiny beasts.

My grandmother, who never learned to drive, had her violets and her cacti, and in summer, her zinnias. Edith, abandoned by her husband Ted, has her cacti. Johnson may be offering some social critique here, some satire even, though it is submerged as subtext.

If Mildred Johnson wrote under a pseudonym, I believe she was a woman nonetheless. I remember the Tiptree fiasco and refrain from any absolute assertion, but Tiptree often wrote from perspectives either male or ambiguous, which allowed her masculine counterparts to convince themselves of the truth they desired. Johnson seems to make a deliberate effort to share a female perspective and a feminine critique.

Abby’s letters meanwhile keep Edith informed of Robert’s increasing and irrational hostility toward the fast-growing plant. Eventually a call comes from the Burdens’ distraught daughter Nancy. With his wife’s grudging permission Robert had attempted to destroy the disturbing interloper with fire, only to have the burning upper half break free and “leap” upon him, impaling him on its spikes. Nancy relates the fate of a father lying dead and disfigured, and the final conscious warning of a mother now bedridden and sedated—the default treatment for women in those days. Heavy sedatives were such a common prescription for American women during that generation—remember “Mother’s Little Helper”—that it is difficult to decide whether Johnson intended this as critique or just the offhand depiction of everyday reality.

Edith gives in to her own trepidations at this point and takes action. Yet fate is fate, and she can only delay her own final confrontation with the cactus.

If “The Cactus” is not a great story, it is still a good one, even an important one, and it deserves an audience. Its subtle—perhaps unintentional—critique of the weird plant trope from a female perspective is memorable. In her tale the weird plant is transposed from a man-eating vegetable in some exotic jungle location to a simple cactus in a domestic setting, a setting that allows a proto-feminist critique, implicit if not deliberate. The extent to which such a critique is intended matters little: it is comprehensible, and it is valid. Whether or not Johnson embedded this consciously or whether it arose as a natural byproduct of her gender lens must remain an enigma. Like “It!” and “Slime,” her tale of transplanted cacti had satisfactory pizzazz to inspire at least one uncredited theft and just enough reprints to preserve it from almost total oblivion.

If “The Cactus” is not a great story, it is still a good one, even an important one, and it deserves an audience. Its subtle—perhaps unintentional—critique of the weird plant trope from a female perspective is memorable. In her tale the weird plant is transposed from a man-eating vegetable in some exotic jungle location to a simple cactus in a domestic setting, a setting that allows a proto-feminist critique, implicit if not deliberate. The extent to which such a critique is intended matters little: it is comprehensible, and it is valid. Whether or not Johnson embedded this consciously or whether it arose as a natural byproduct of her gender lens must remain an enigma. Like “It!” and “Slime,” her tale of transplanted cacti had satisfactory pizzazz to inspire at least one uncredited theft and just enough reprints to preserve it from almost total oblivion.

“The Cactus” is available at no cost online, but for those who prefer physical books, the volume 100 Creepy Little Creature Stories is not that hard to come by, and readers of this series will likely find much to interest them in that collection.

Of course, Stories From the Borderland is a collaborative project, and my partner Michael Bukowski’s illustration of “the cactus” may be seen simply by following this link.

Next week we dip back into Weird Tales for the pulpy narrative of a relentless antagonist and his slippery pursuit, a tale that inspired two sequels and a cover. Soggy as this story may seem today, it hit like a tiny tidal wave in its time.