Who was Margaret St. Clair? The available details of her biography provide barely more than an outline. Feminist, Wiccan, she wrote and published freely in the postwar era, which was very much a man’s world. She employed two pseudonyms, Idris Seabright and Wilton Hazzard, but the first is obviously feminine and she rarely used the latter. She is most often remembered today for two stories: the oft-anthologized “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles,” easily the best Dunsany pastiche ever, and “Brenda.”

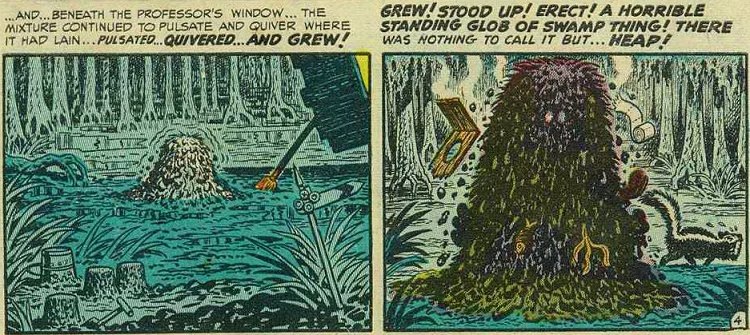

“Brenda” is a story in the long lineage of muck men and swamp monsters, which runs back as far as H.R. Wakefield’s 1928 “The Red Lodge,” but explodes after Theodore Sturgeon’s “It” in 1940. “It” is the cousin of Joseph Payne Brennan‘s “Slime” (Stories from the Borderland #1) and the immediate ancestor of “The Heap.” Heap in turn inspired Swamp Thing, Man-Thing, Bugs Bunny’s interesting nemesis Gossamer, and at least a dozen others. My personal favorite appeared in the fifth issue of the original MAD comic magazine in 1953, where the origin of Heap provides the parody within a parody of the old radio series Inner Sanctum.

“Brenda” focuses not so much on its muck man however, as on its titular character, a young girl nearly as singular and unpleasant as the foul-smelling creature she encounters in the woods. It’s a good story, one of St. Clair’s creepier works, and definitely weird, but the reason it is well remembered is it was adapted for Rod Serling’s Night Gallery in 1971. One of the weirder and more memorable episodes, in fact, if not up to the iconic status of “The Caterpillar.”

“Brenda” focuses not so much on its muck man however, as on its titular character, a young girl nearly as singular and unpleasant as the foul-smelling creature she encounters in the woods. It’s a good story, one of St. Clair’s creepier works, and definitely weird, but the reason it is well remembered is it was adapted for Rod Serling’s Night Gallery in 1971. One of the weirder and more memorable episodes, in fact, if not up to the iconic status of “The Caterpillar.”

Michael Bukowski, my partner in this project, found so much inspiration in St. Clair’s work that he felt compelled to offer two illustrations with this installment, so you can see an image of Brenda’s rotten-smelling man at his blog [link], along with a creature from the story that is our actual subject this week. If you have seen the Night Gallery episode, you will see that Michael chose to present the creature as he appears in the original story, a humanoid muck man, rather than the TV version, an amorphous and leafy swamp monster that defaults back to The Heap…and looks suspiciously like the basis for Sid and Marty Krofft’s Sigmund and the Sea Monsters two years later. But “Brenda” is only a prelim. Let us move on to this week’s main attraction.

A scene from The Night Gallery episode of “Brenda.” The TV version, an amorphous and leafy swamp monster, defaults back to The Heap.

Michael and I recently discussed how much we enjoy all the unexpected connections we encounter while researching the stories for this series. We approach most of these stories as relatively simple, pulpy, and isolated tales, and before we are done, we find them embedded in webs of references and relations. This has been a surprise for us as well as a reward.

Allusion comes immediate and explicit in “Horrer Howce,” right in the opening paragraph, as Dickson-Hawes, one of only two speaking characters in the story, first mentions Yeats by name then loosely quotes—or rather misquotes—“The Second Coming,” referencing a “monstrous beast” rather than a “rough beast.” The investor’s inspiration for this poetic outburst came from what he saw beyond a small panel in the wall, a “monstrous womb, alone on the seashore, slowly swelling.” The womb and whatever he saw emerge from it comprised one of Freeman’s under-development attractions for a nationwide series of horror houses Dickson-Hawes is planning.

Allusion comes immediate and explicit in “Horrer Howce,” right in the opening paragraph, as Dickson-Hawes, one of only two speaking characters in the story, first mentions Yeats by name then loosely quotes—or rather misquotes—“The Second Coming,” referencing a “monstrous beast” rather than a “rough beast.” The investor’s inspiration for this poetic outburst came from what he saw beyond a small panel in the wall, a “monstrous womb, alone on the seashore, slowly swelling.” The womb and whatever he saw emerge from it comprised one of Freeman’s under-development attractions for a nationwide series of horror houses Dickson-Hawes is planning.

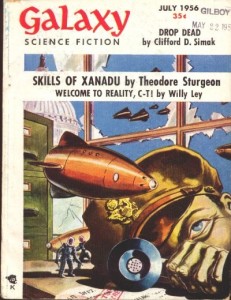

I am tempted to consider this peephole vision of a faceless feminine form as another allusion, to Marcel Duchamp’s final masterpiece, Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’éclairage (for which I was once ejected by security from the Philadelphia Museum of Art after sneaking in to view while the exhibit was closed), but Duchamp’s assemblage made no public appearance until 1969, while St. Clair’s story first appeared in the July 1956 issue of Galaxy. Any resemblance must be coincidence unless she had some personal relationship with Duchamp. Possible, but in so far as I know, undocumented. Synchronicity is all. We run into a lot of that here too.

Dickson-Hawes decides to pass on this potential feature however, despite its obviously powerful effect on him, forcing Freeman to extend the tour to other projects, less polished and more…dangerous. Safety railings in Freeman’s funhouse attractions seem as scant as those in the Star Wars universe, and he feels the need to admonish his client multiple times to keep his voice down so as not to disturb the delicate “machinery” of the attractions. Freeman implies there have been “incidents” in the past.

“What happens if I keep leaning over? Or if I drop pebbles down on it?”

“It’ll come out at you.”

As the two men advance from “The Well” to the “Horrer Howce” their conversation reveals more of the economic dynamics between them. Despite his almost otherworldly skill with electronics: “Particularly radio and signaling devices. Relays. Communication problems, you might say,” Freeman is up against a wall. He has a “political past,” and Dickson-Hawes is his last potential buyer. A political past suggests Freeman ran afoul of the House Un-American Activities Committee and found himself blackballed. The McCarthy hearings were barely two years concluded when St. Clair first published “Horrer Howce,” and the witch hunts still reverberated through the American psyche (the HUAC itself continued as a standing committee until 1975). To complicate Freeman’s position further, Dickson-Hawes is his only remaining potential buyer.

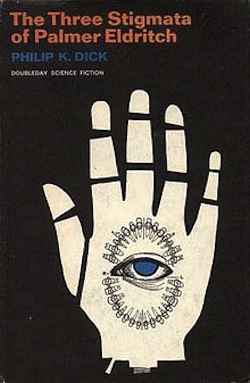

Much of St. Clair’s best work—and her weirdest work—engages in a potent critique of postwar American society, with an emphasis on the rampant consumer culture that took off during that era and has dominated our society ever since. In stories such as “Gnoles,” “Horrer Howce,” and “An Egg a Month From All Over,” she satirized the same mercantile values as the cable series Mad Men, but it is “Horrer Howce” that most simply and elegantly demonstrates how the crosshairs of political oppression and cutthroat capitalism can drive a person to open strange doors. She uses The Weird as a tool for social criticism in much the same way, and with the same targets, that Philip K. Dick would do a decade later in his own weird masterpiece The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch.

St. Clair began the story with a long finger pointed directly at “The Second Coming.” Returning to Yeats’ poem after one has read all of “Horrer Howce,” this couplet inevitably leaps out:

St. Clair began the story with a long finger pointed directly at “The Second Coming.” Returning to Yeats’ poem after one has read all of “Horrer Howce,” this couplet inevitably leaps out:

Mere Anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed

Whether or not Freeman makes his sale, doors are now open that should have stayed closed. But an entrepreneur with his special skills at “communication” can find customers on either side.

Please keep as quiet as possible as you go through this next door, where Michael Bukowski is waiting to introduce you to the Voom: https://yog-blogsoth.blogspot.com/2016/04/voom.html. Say hello, shake hands. You pays your money, you takes your chance.

There are fish stories, and there are fishy stories. Please join us again next week, when our fourth episode in the second series of Stories From the Borderland brings you a story that’s plenty of both, by an author who, like me, began publishing late. One of the last dangerous visionaries, you might say, whose brief career left barely more than a dozen stories, though every one of them is razor sharp. Guess the answer, win a prize. Come on in, the water’s fine.