A mysterious resident of Manitoba named John E. Wall coined the term “cryptid” in a 1983 letter to the newsletter of the now-defunct International Society of Cryptozoology. Credit for the coinage of “cryptozoology” goes to either Ivan T. Sanderson, Bernard T. Heuvelmans, or Lucien Blancou. Though the word’s exact origins are appropriately unclear, it definitely appeared in print by 1959. The first usage of “weird” in the literary sense now familiar to us belongs either to Sheridan LeFanu in the late nineteenth century or H.P. Lovecraft in the early twentieth. Cryptids and cryptozoology however, have been fixtures of Weird Fiction since long before popular culture cemented any of these terms in their current forms and denotations.1

A mysterious resident of Manitoba named John E. Wall coined the term “cryptid” in a 1983 letter to the newsletter of the now-defunct International Society of Cryptozoology. Credit for the coinage of “cryptozoology” goes to either Ivan T. Sanderson, Bernard T. Heuvelmans, or Lucien Blancou. Though the word’s exact origins are appropriately unclear, it definitely appeared in print by 1959. The first usage of “weird” in the literary sense now familiar to us belongs either to Sheridan LeFanu in the late nineteenth century or H.P. Lovecraft in the early twentieth. Cryptids and cryptozoology however, have been fixtures of Weird Fiction since long before popular culture cemented any of these terms in their current forms and denotations.1

These monsters that straddle myth and the modern have been mainstays of The Weird from such early classics as Algernon Blackwood’s “The Wendigo,” William Hope Hodgson’s “A Tropical Horror,” H.G. Wells’ “In the Avu Observatory,” and H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Whisperer in Darkness” to more recent favorites like Edward Morris’ sasquatch tale “Lotophagi” and the title story of Nathan Ballingrud’s Shirley Jackson Award-winning debut collection North American Lake Monsters. Some authors built large bodies of work around the study of “hidden creatures,” as in the Brigadier Ffellowes stories of Sterling Lanier, or most notably, the fiction of Manly Wade Wellman. I myself have included cryptids in my work several times, and Michael and I have already veered into territory both cryptozoological and cryptobotanical here in Stories from the Borderland.

I have no interest in attempting to explain or define this relationship between cryptids and Weird Fiction, and adjectives such as “natural” or “unsurprising” have no place in this frame. As concepts in our thoughts they have grown together from the same deep roots. The Weird is the forest whose shadows rise just beyond the reach of our firelight. Cryptids are the eyes that stare back in uncouth configurations from its treetops.2 Together they compose an ecology of the unexplained.

I have no interest in attempting to explain or define this relationship between cryptids and Weird Fiction, and adjectives such as “natural” or “unsurprising” have no place in this frame. As concepts in our thoughts they have grown together from the same deep roots. The Weird is the forest whose shadows rise just beyond the reach of our firelight. Cryptids are the eyes that stare back in uncouth configurations from its treetops.2 Together they compose an ecology of the unexplained.

Many authors have also employed the trappings of Forteana and cryptozoology to present their own “hidden creatures,” as in Lovecraft’s “Whisperer in Darkness,” which opens with the already standard formula of indigenous legend, elusive sightings, and the tantalizing possibility of tangible evidence. This dialogue between the domains is ultimately a two-way street, as evidenced by how many times Arthur Conan Doyle’s “giant rat of Sumatra” has actually been discovered, or how quickly the online community leapt to point out the proximity of the coordinates for the mysterious underwater sound known as the Bloop to those of Lovecraft’s fictional sunken city R’lyeh.

Meanwhile from Blackwood to Ballingrud, and from sea monster to lake monster, yeti to kongamoto, virtually every major cryptid has appeared somewhere in Weird Fiction at least once. One of the first to get the literary treatment was Australia’s flagship mystery critter, the bunyip.

Meanwhile from Blackwood to Ballingrud, and from sea monster to lake monster, yeti to kongamoto, virtually every major cryptid has appeared somewhere in Weird Fiction at least once. One of the first to get the literary treatment was Australia’s flagship mystery critter, the bunyip.

Though it lacks the global recognition of Nessie or Bigfoot, the bunyip or “yowie” has been a fixture of European-Australian culture since the mid-nineteenth century. Predictably, early European immigrants appropriated their version of the bunyip from older stories belonging to the indigenous Aboriginal people. I recently spent several weeks excavating a Terminal Classic Maya house site on a hilltop in the Chiquibul Forest of Belize under the supervision of an archaeologist from Australia, and she readily attested both to the bunyip’s ongoing notoriety in her homeland as well as its profound and continued significance to Aboriginal culture. My friend was unfamiliar with Rosa Campbell Praed however, though not through any fault of her own. “Every one who has lived in Australia has heard of the Bunyip. It is the one respectable flesh-curdling horror of which Australia can boast,” wrote Rosa Campbell Praed in 1891. Australians may all know the bunyip, but one of their first major English-language authors remains largely forgotten.

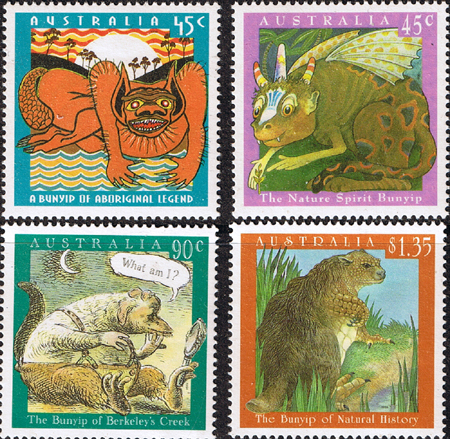

As Michael Bukowski discovered from his research for this installment, the bunyip has appeared on at least four Australian postage stamps; Rosa Campbell Praed on none. Then again, despite publishing almost fifty books between 1880 and 1916, over half of them set in Australia, Mrs. Praed abandoned her homeland at the age of 25 and returned only once thereafter. The bunyip on the other hand appears to be a permanent resident, one still sighted at least as frequently as Nessie or Ogopogo. Probably a venerable one as well, given the considerable resemblance between certain descriptions of the bunyip and reconstructions of such Pleistocene epoch marsupial megafauna as Diprotodon, Zygomaturus, Nototherium, and Palorchestes—extinct giant relatives of the wombat and koala (wombats might not seem particularly scary, especially by Ozzie standards, but my archaeologist friend assured me that even today’s scaled-down variety will fuck your car up pretty seriously if you hit one—and Diprotodon was the size of a car). Depending on one’s degree of cryptological skepticism, such resemblances may be due either to encounters with the bones of these long-vanished creatures, or strange survivals into recent times.

As Michael Bukowski discovered from his research for this installment, the bunyip has appeared on at least four Australian postage stamps; Rosa Campbell Praed on none. Then again, despite publishing almost fifty books between 1880 and 1916, over half of them set in Australia, Mrs. Praed abandoned her homeland at the age of 25 and returned only once thereafter. The bunyip on the other hand appears to be a permanent resident, one still sighted at least as frequently as Nessie or Ogopogo. Probably a venerable one as well, given the considerable resemblance between certain descriptions of the bunyip and reconstructions of such Pleistocene epoch marsupial megafauna as Diprotodon, Zygomaturus, Nototherium, and Palorchestes—extinct giant relatives of the wombat and koala (wombats might not seem particularly scary, especially by Ozzie standards, but my archaeologist friend assured me that even today’s scaled-down variety will fuck your car up pretty seriously if you hit one—and Diprotodon was the size of a car). Depending on one’s degree of cryptological skepticism, such resemblances may be due either to encounters with the bones of these long-vanished creatures, or strange survivals into recent times.

Of course Rosa Campbell Praed is only one of many once popular and successful authors of her time to sink into obscurity. Her even more prolific and far more successful contemporary Robert W. Chambers, would be utterly forgotten now if not for the handful of stories he wrote about the King in Yellow and the Yellow Sign. Herman Melville himself almost suffered such a fate. Others were less fortunate. Oblivion has claimed them, tout entière. Stories from the Borderland is, in part, about rescuing some of these stories from the edge of the abyss.

Of course Rosa Campbell Praed is only one of many once popular and successful authors of her time to sink into obscurity. Her even more prolific and far more successful contemporary Robert W. Chambers, would be utterly forgotten now if not for the handful of stories he wrote about the King in Yellow and the Yellow Sign. Herman Melville himself almost suffered such a fate. Others were less fortunate. Oblivion has claimed them, tout entière. Stories from the Borderland is, in part, about rescuing some of these stories from the edge of the abyss.

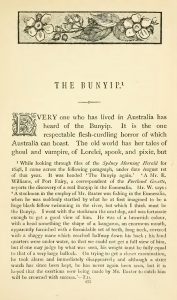

There are reasons why so little of Praed’s work has stood the test of time. The social, spiritual, and political themes that occupied much of her writing are no longer relevant. “The Bunyip” however, retains some freshness and is an interesting story in several ways. That said, though Praed was known in her day as a rare advocate for indigenous civil rights, her portrayal of the Aboriginal people is terribly patronizing and dated. Technically and stylistically however, the tale holds up rather well. Though structured along the narrative arc of a short story, Praed presents her material as memoir, even going so far as establishing an air of veracity via a footnote off the title that references an 1848 article about the bunyip in the Sydney Morning Herald. The whole thing feels a bit like a little Australian X-Files episode.

What really makes “The Bunyip” stand out however, are the elements that also make it Weird. Praed displays a deft mastery for the creation of both verisimilitude and a multi-sensory atmosphere, as in this passage from the second paragraph (exclusive of the aforementioned footnote), which also shows her natural ability to frame a story:

What really makes “The Bunyip” stand out however, are the elements that also make it Weird. Praed displays a deft mastery for the creation of both verisimilitude and a multi-sensory atmosphere, as in this passage from the second paragraph (exclusive of the aforementioned footnote), which also shows her natural ability to frame a story:

“Some night, perhaps, when you are sitting over a camp fire brewing quart-pot tea and smoking store tobacco, with the spectral white gums rising like an army of ghosts around you, and the horses’ hobbles clanking cheerfully in the distance, you will ask one of the overlanding hands to tell you what he knows about the Bunyip.”

Or this one, as we get closer to the action:

“This lagoon is about four miles long, in some parts very deep, in others nothing but marsh, with swamp-oaks and ti-trees and ghostly white-barked she-oaks growing thickly in the shallow water. The wild-duck is so numerous in places that a gun fired makes the air black, and it is impossible to hear oneself speak, so deafening are the shrill cries of the birds which brood over the swamp.”

Writing like this is as good as any in early Weird Fiction. Compare it for instance to that great opening atmosphere passage of Blackwood’s “The Willows,” arguably the ur-Weird Tale. From here the story builds frantically to a tragic conclusion and a denouement more than mysterious and inexplicable enough to establish its Weird bona fides.

Writing like this is as good as any in early Weird Fiction. Compare it for instance to that great opening atmosphere passage of Blackwood’s “The Willows,” arguably the ur-Weird Tale. From here the story builds frantically to a tragic conclusion and a denouement more than mysterious and inexplicable enough to establish its Weird bona fides.

The final eerie image of “The Bunyip,” a lone and sinister tree, holds special appeal to both Michael and me, as it recalls a similar image in one of the most perfect of all Weird Tales: “The Dead Valley” by celebrated American architect Ralph Adams Cram. Our shared love for the latter story is one of the things that first brought us together as collaborators. The text of both stories is available online; we will leave you to make any comparisons for yourself. Interestingly, Cram’s story was published only four years after Praed’s. We are not suggesting any relationship or influence, but perhaps there was something in the air (other than the ashes of Krakatoa)…

Although this may be the first episode of Stories from the Borderland in which Michael and I have explicitly framed our project as a kind of literary cryptozoology, that description is as good as any for what we are about here. We appreciate the response we have had from so many readers, and we hope to continue tracking down previously unidentified species of The Weird…and bringing them back to you alive.

Although this may be the first episode of Stories from the Borderland in which Michael and I have explicitly framed our project as a kind of literary cryptozoology, that description is as good as any for what we are about here. We appreciate the response we have had from so many readers, and we hope to continue tracking down previously unidentified species of The Weird…and bringing them back to you alive.

Those of you who attended our presentation of Stories from the Borderland Live at NecronomiCon 2017 in Providence got to preview Michael’s vision of the Bunyip, but now everyone can see it here (and you can all hear our NecronomiCon presentation on The Outer Dark here). SFTB returns next week with a rare bit of creepy crawly haberdashery from one of the most celebrated living authors in speculative fiction. As always, if you can guess the story in advance, you may win a prize (contest not open to employees of Stories from the Borderland or their families, sj bagley, Justin Steele, or Marc Laidlaw).

1https://lorencoleman.com/the-meaning-of-cryptozoology/

1https://lorencoleman.com/the-meaning-of-cryptozoology/

https://cryptomundo.com/cryptozoo-news/cryptid/

2I recently returned from a month sleeping in a hammock in the jungle. Let me tell you about some of the noises you hear out there around 3:00 a.m.

Leave a Reply